Unconscious bias

Unconscious biases are mental “shortcuts” that our brains use to make sense of the world around us. We all have unconscious biases, but by slowing down and becoming aware of them, we can reduce their impact on our decisions.

Not all bias is unconscious. Unfortunately, it is still all too common for people to experience overt discrimination based on their race, gender, sexuality, disability, or other aspects of their identity.

Unconscious bias

We all have unconscious biases. Because our brains take in more information than they can process, we rely on mental shortcuts to simplify the world around us—which means we rely on stereotypes.

Sometimes, stereotypes are helpful. If an animal is running toward you in the woods, you don’t take the time to carefully evaluate it to confirm that it’s a bear. You make a snap judgment. But when we rely on snap judgments about people, the results can be very harmful.

Experts at Harvard developed what are called IATs, or Implicit Association Tests, to better understand the unconscious biases we commonly hold. The results are eye-opening: 76 percent of participants more readily associate men with career and women with family, regardless of their own gender, and 75 percent of participants show a preference for white people over Black people—regardless of their own race.

It’s hard to admit that we hold these biases, but it’s important to remember that no one is immune from them. We all have work to do.

It’s also important to remember that not all bias is unconscious. Many people experience overt discrimination based on their race, gender, sexuality, disability, or other aspects of their identity. Unfortunately, these experiences are real, and they are still all too common.

Performance bias

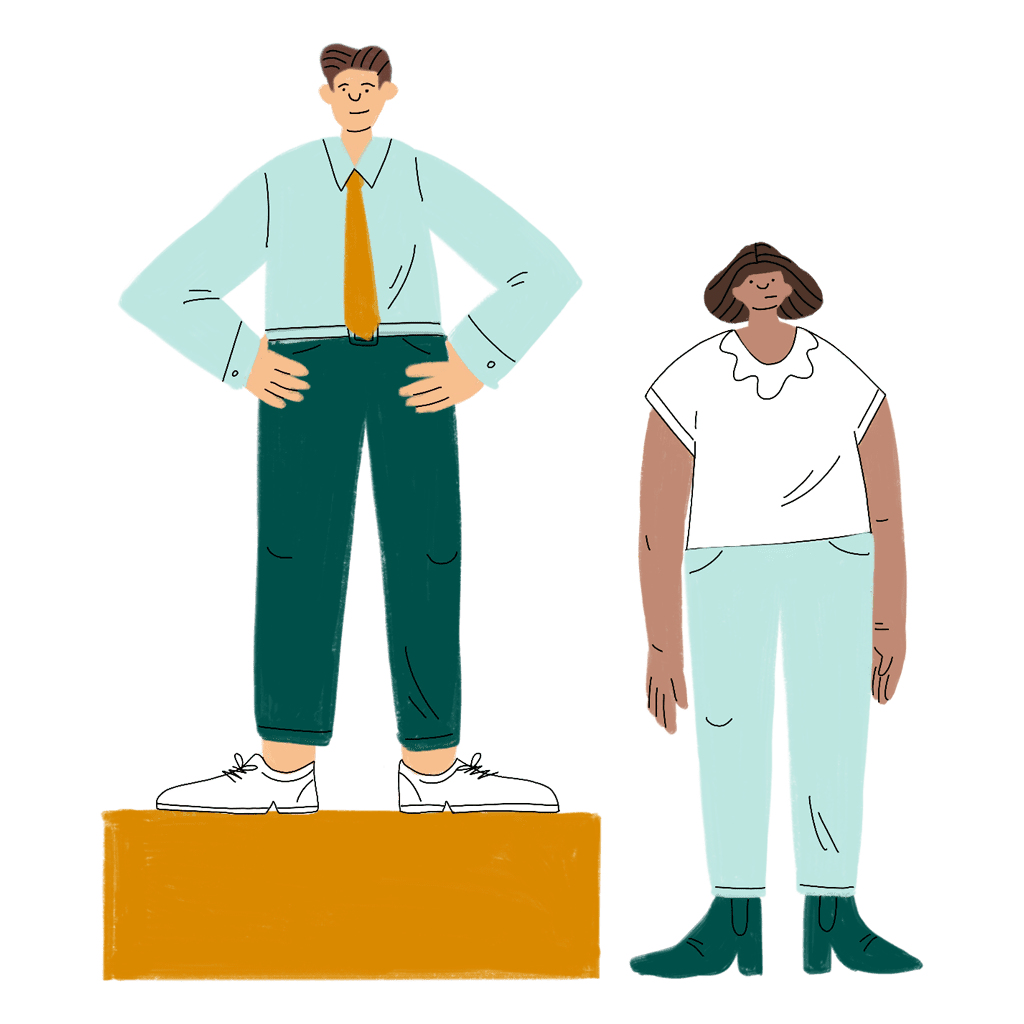

Performance bias is based on deep-rooted—and incorrect—assumptions about women’s and men’s abilities. We tend to underestimate women’s performance and overestimate men’s.14

Performance bias

We tend to underestimate women’s performance and overestimate men’s. As a result, women have to accomplish more to prove that they’re as competent as men. This is why women are often hired based on past accomplishments (they need to prove that they have the right skills), while men are often hired based on future potential (we assume they have the skills they need).15

Women with disabilities and women of color, particularly Latinas and Black women, experience this bias even more often than other women. They are more likely to have their judgment and competence questioned and to hear others express surprise at their language skills or other abilities.16

To understand the impact of this bias, consider what happens when you remove gender from decision-making. In one study, replacing a woman’s name with a man’s name on a résumé improved the odds of getting hired by more than 60%.17 In another, when major orchestras used blind auditions—so they could hear the musicians but not see them—the odds of women making it past the first round improved by 50%.18

Performance bias often leads to missed opportunities and lower performance ratings for women—and both can have a huge impact on career progression.19 This bias is even more pronounced when review criteria aren’t clearly specified, leaving room for managers and others to rely more on gut feelings and personal inferences.20

Attribution bias

Attribution bias is closely linked to performance bias. Because we see women as less competent than men, we tend to give them less credit for accomplishments and blame them more for mistakes.21

Attribution bias

Because we see women as less competent than men, we don’t always recognize the work they do. Even when women and men work on tasks together, women often get less credit for success and more blame for failure.22

We also fall into the trap of thinking women’s contributions are less valuable. This often plays out in meetings, where women are more likely to be talked over and interrupted.23 In one study, men interrupted women nearly three times as often as they interrupted other men, and women fell into the same pattern.24

Given that women are often blamed more for failure and tend to wield less influence, they are prone to greater self-doubt. The bias women experience can be so pervasive that they underestimate their own performance. Women often predict that they’ll do worse than they actually do, while men predict that they’ll do better.25

In some cases, women are also less likely to think they’re ready for a promotion or new job. One study found that men apply for jobs when they meet 60% of hiring criteria, while women wait until they meet 100%.26 Of course, women don’t lack a confidence gene. Given we hold women to higher standards, women may rightfully feel like they have to hit a higher bar.

Likeability bias

Likeability bias is rooted in age-old expectations. We expect men to be assertive, so when they lead, it feels natural. We expect women to be kind and communal, so when they assert themselves, we like them less.27

Likeability bias

Likeability bias—also known as the “likeability penalty”—often surfaces in how we describe women. Women are more likely to be described as “too aggressive” or “bossy”—words rarely used to describe men in the workplace.28

You may even have caught yourself having a negative response to a woman who has a strong leadership style or who speaks in a direct, assertive manner. This is likeability bias at work. And being liked matters. Who are you more likely to support and promote: the man with high marks across the board or the woman who has equally high marks but is not as well liked?

To make things more complicated, women also pay a penalty for being agreeable and nice, which can make people think they’re less competent.29 This double bind makes the workplace challenging for women. They need to assert themselves to be seen as effective. But when they do assert themselves, they are often less liked. Men do not walk this same tightrope.30

This bias plays out differently, but no less damagingly, for women of color. Black women are more likely to trigger this penalty in many workplace contexts because they are more often stereotyped as angry and aggressive. Meanwhile, Asian American women are more often stereotyped as being communal than other groups of women, and this can make people less likely to see them as effective leaders.31

Maternal bias

Motherhood triggers false assumptions that women are less committed to their careers—and even less competent.32

Maternal bias

We incorrectly assume that mothers are less committed and less competent. As a result, mothers are often given fewer opportunities and held to higher standards than fathers.33

We fall into the trap of thinking mothers are not as interested in their jobs, so we assume they don’t want that challenging assignment or to go on a big work trip. And because we think they’re less committed, we’re more likely to penalize them for small mistakes or oversights.34

Research shows that maternal bias is the strongest type of gender bias.35 When hiring managers know a woman has children—because “Parent-Teacher Association coordinator” appears on her résumé—she is 79% less likely to be hired. And if she was hired, she would be offered an average of $11,000 less in salary.36

Men can face pushback for having kids, too. Fathers who take time off for family reasons receive lower performance ratings and experience steeper reductions in future earnings than mothers who do.37

Affinity bias

Affinity bias is what it sounds like: we gravitate toward people like ourselves in appearance, beliefs, and background. And we may avoid or even dislike people who are different from us.38

Affinity bias

Because of affinity bias, we often gravitate toward people like ourselves—and may avoid or even dislike people who are different.39

Affinity bias plays out in several ways in the workplace. Mentors say they’re attracted to protégés who remind them of themselves.40 And hiring managers are more likely to spend time interviewing people who are like them and less time getting to know people who are different.41 They are also more likely to give people like them a favorable evaluation.42

Because straight white men hold more positions of power—and are more likely to gravitate toward other white men—affinity bias has a particularly negative effect on women, people of color and LGBTQ employees.43

Intersectionality

Bias isn’t limited to gender. Women can also experience biases due to their race, sexual orientation, a disability, or other aspects of their identity.

Intersectionality

Women can also experience biases due to their race, sexual orientation, a disability, or other aspects of their identity—and the compounded discrimination can be significantly greater than the sum of its parts.

For example, women of color often face double discrimination: biases for being women and biases for being people of color. Compared to white women, women of color receive less support from managers, get less access to senior leaders, and are promoted more slowly.44 As a result, they are particularly underrepresented in the corporate pipeline, behind white men, white women, and men of color.45

A similar dynamic holds true for LGBTQ women. Research shows that lesbians have a harder time securing employment than women more broadly.46

When different types of discrimination interconnect and overlap, this is called intersectionality.47 Imagine the compounded effect of being Black, Muslim, an immigrant, and a woman. Research shows people with three or more marginalized identities often feel like they don’t belong anywhere.48 Each card in this pack includes a reminder about intersectionality because it’s critical that we’re aware of the different biases people can experience and commit to fairness for everyone.

Microaggressions

Microaggressions are comments and actions that demean or dismiss someone based on their gender, race, or other aspects of their identity. They are often rooted in various types of both conscious and unconscious bias and can range from subtle slights to explicit disrespect.

Microaggressions

Microaggressions are a form of day-to-day discrimination directed at those with less power. They are an all-too-common occurrence in the workplace and are often rooted in various types of bias—for example, performance bias may lead colleagues to question a woman’s judgment in her area of expertise or mistake her for someone at a more junior level. And because women experience more types of bias at work, they also face a wider range of microaggressions than men.

For women with other marginalized identities, such as women of color and LGBTQ+ women, microaggressions are often even more pronounced. Compared to women of other races and ethnicities, Black women are nearly two and a half times more likely than white women—and more than three times more likely than men—to hear someone in their workplace express surprise about their language skills or other abilities. Lesbian women, bisexual women, and women with disabilities are far more likely than other women to hear demeaning remarks about themselves or others like them and to feel that they can’t talk about their personal lives at work.

Microaggressions may seem insignificant when viewed as isolated incidents. But when they occur day after day—as they often do—their impact builds up and takes a toll. Whether intentional or unintentional, these insults and invalidations signal disrespect. It’s hard for any employee to bring their best self to work when they’re often underestimated and slighted. Women who experience microaggressions are three times more likely to regularly think about leaving their job than those who don’t.

Use this set to run an introductory workshop for all employees, or for any group that wants to focus on understanding the fundamentals of workplace bias.

Use this set to provide managers with concrete steps for fighting bias and creating an inclusive team culture.

Use this set to help senior leaders understand how they can fight bias by shifting company policies, programs, and culture.

Use this set to educate employees about the biases women of color face at work and the concrete steps colleagues can take to interrupt bias and practice allyship.

Use this set to learn how to address bias in hiring and promotions at the first step up to manager—the “broken rung” where women are often overlooked and left behind.

Use this set to educate interviewers, recruiters, and hiring managers on how to recognize and reduce bias in the hiring process.

Use this set to train evaluators on reducing bias in reviews and promotions—an area where biased assessments can have a big impact on women’s careers.

Use this set to educate employees about the powerful and damaging biases that working mothers often face.

Use this set to help employees set inclusive norms, approach coworkers with empathy, and push back on acts of bias.

Use this set to educate employees on how bias can affect workplace relationships, including mentorship, sponsorship, networking opportunities, and access to senior leaders.

Use this set to help employees understand and combat the effects of bias in remote work environments.

Use this set to educate employees on the compounding biases faced by LGBTQ+ women, women of color, Muslim women, immigrant women, and women with disabilities.

Welcome to the 50 Ways to Fight Bias digital program

Welcome to 50 Ways to Fight Bias, a free digital program to empower all employees to identify and challenge bias head on. Here, we’ll give you everything you need to prepare for and run a successful workshop at your company—and you can learn more about different ways to implement one at your company here.

You can access these two sections at any time using the menu on the left. And as you go through the program, anytime a menu item is mentioned it will be highlighted in bold.

How to get setup

Each 50 Ways to Fight Bias workshop consists of four steps that you will guide participants through. You can access any section using the menu on the left under Run your workshop.

Set the tone

All 50 Ways workshops begin by level setting with participants on how to encourage an open and respectful discussion.

What you need to do: Use our to walk through this part of the program.

Introduction to bias

Participants watch a short video that explains the most common types of biases that women face as well as the concept of intersectionality—how women can experience compounding biases due to other aspects of their identity.

What you need to do: We recommend having participants watch our 12-minute bias overview video. Alternatively, you can ask participants to read about bias types on the same page.

Group activity

Participants break into small groups to review specific examples of bias—and why each one matters. They take a few minutes to discuss each situation and brainstorm solutions for interrupting the bias. They then learn what experts recommend they do in that situation, along with a short explanation of what's behind the bias.

What you need to do: Before the workshop begins, select a set of digital cards on the Choose a set page that participants will discuss in your workshop.

Decide how to divide participants into mixed-gender groups of 6-8 people. If you’re running a virtual workshop, we recommend that you use breakout rooms—and we have more tips for running this virtually in our speaker notes.

Commit to action

As the activity wraps up, participants commit to take One Action to fight bias based on what they learned.

What you need to do: Use our speaker notes to get prepared for this part of the program.

Now that you know how to get set up, continue to:

FINAL STEPSFinal steps

You are almost ready to run your 50 Ways to Fight Bias workshop! Before you start your session, make sure you have taken the steps below.

Set of digital cards selected

After you’ve selected a set of digital cards, you can find your set in the menu on the left to walk through live in your workshop. You can also download a PDF version on the Choose a set page if you’re running your workshop offline.

Speaker notes downloaded

Our speaker notes walk you through what to say as you run your workshop. It also provides some best practices for leading virtual workshops.

Need more time? Come back to this digital program when you’re ready and select Run your workshop in the menu on the left.

Workshop agenda

Welcome to 50 Ways to Fight Bias, a free digital program to empower all employees to identify and challenge bias head-on. Today’s activity will help you recognize and combat the biases women face at work. It is divided into four parts:

Set the tone

Introduction to bias

Group activity

Commit to action

Guiding principles

Bias is complex, and counteracting it takes work. As you engage with the situations in this activity, remember that:

Bias isn’t limited to gender

People also face biases due to their race, sexual orientation, disability, or other aspects of identity—and the compounding discrimination can be much greater than the sum of its parts. This is called intersectionality, and it can impact any situation.

Knowing that bias exists isn’t enough

We all need to look for it and take steps to counteract it. That's why this activity outlines specific examples of the biases women face at work with clear recommendations for what to do.

We all fall into bias traps

People of all genders can consciously or unconsciously make biased comments or behave in other ways that disadvantage women.

Give people the benefit of the doubt

Remember that everyone is here to learn and do better—and an open and honest exchange is part of that process.

Stories should be anonymous

When sharing stories about seeing or experiencing bias, don’t use people’s names.

Some situations may be difficult to hear

Be mindful that some of the situations described in this program may be sensitive or painful for participants.

Learn about bias types

This section covers the most common types of biases that women face at work. Watch the overview video or select a bias type below to learn more about what it is, why it happens, and why it’s harmful.

Play the video An introduction to the common biases women experience (12 minutes)

Overview of key concepts

As you learn more about bias, it’s important to be aware of two key concepts: intersectionality, or how women can experience compounding biases due to other aspects of their identity, and microaggressions, which are subtle or explicit comments and actions that signal disrespect. Click the tiles below for a detailed explanation of each concept.

Summary: Strategies to fight bias

There are a number of ways to respond to bias when it occurs. Below is a summary of the strategies we’ve discussed today:

-

1

Speak up for someone in the moment

For example, remind people of a colleague’s talents or ask to hear from someone who was interrupted. Or when someone says something incorrect (e.g., assumes a woman is more junior than she is), matter-of-factly correct them—either in the moment or in private later.

-

2

Ask a probing question

Ask a question that makes your colleague examine their thinking—“What makes you say that?” “What are some examples of that?” This can help people discover the bias in their own thinking.

-

3

Stick to the facts

When you can, shift the conversation toward concrete, neutral information to minimize bias. For example, if someone makes a subjective or biased comment in a hiring or promotions meeting, refocus attention back to the list of criteria for the role.

-

4

Explain how bias is in play

Surface hidden patterns you’ve observed and explain what they mean. Research shows that a matter-of-fact explanation can be an effective way to combat bias. For example, mention to a hiring committee that you've noticed they tend to select men over women with similar abilities, or point out to your manager that women are doing more of the "office housework."

-

5

Advocate for policy or process change

Talk to HR or leadership at your company and recommend best practices that reduce bias.

Closing activity

Today you’ve heard about a lot of different actions you can take to fight bias in your workplace. Now it’s time to put what you’ve learned into practice.

- Think of one thing you’re going to do when you see bias at work—or one thing that you’ve learned that you’re going to share with others.

- Write it down. This is your “One Action.”

- Taking turns, go around the group and share your One Action.

- Thank you for participating in this 50 Ways to Fight Bias workshop—and for doing your part to create a more inclusive workplace for all.

1 Choose your Icebreakers

2 Choose your cards

Filter by...

Situation & Bias Type Identity

0 available cards

3 Order your deck of cards

From the cards you’ve selected, click and drag them into the order you would like to present. We recommended that you start with situations that are more comfortable for your audience to discuss, followed by those that may be more difficult. Icebreakers always come before Bias cards.

Icebreaker cards

Bias Cards

Sorry, customizing a set is not supported on small screens.

Go back to Set selectionWhen 1 in 10 senior leaders at their company is a woman, what % of men and what % of women think women are well represented in leadership?

Did you know?

Guess the answer as a group.

44% of men and 22% of women.175

What % of women have experienced workplace microaggressions (everyday sexism like being mistaken for someone more junior or having their competence questioned)?

Did you know?

Guess the answer as a group.

73%. 347

What percentage of C-suite executives in the United States are women of color?

Did you know?

Guess the answer as a group.

Answer: 4%—despite being 18% of the U.S. population

In a study of performance reviews, what % of women received negative feedback on their personal style such as “You can sometimes be abrasive”? And what % of men received that same type of feedback?

Did you know?

Guess the answer as a group.

66% of women and 1% of men.50

A colleague is talking about a woman who landed a big project. They say, “Wow, she got really lucky.”

Why it matters

Getting recognized for accomplishments can make a difference, especially when it comes to performance reviews and promotions.172 When achievements are attributed to luck rather than hard work or skill, it minimizes them.

What to do

Ask your colleague, “I’m curious—what makes you think it was luck?” This may prompt them to slow down and rethink their assumption. If your colleague responds in a way that suggests they doubt the woman’s abilities, you might want to press more and ask why they think she’s less competent. Is there a reason? Can they give an example? If not, that speaks for itself.

Why it happens

We tend to overestimate men’s performance and underestimate women’s.173 Because of this, we often attribute women’s successes to “getting lucky,” “having a good team,” or other explanations that diminish their achievements, while we accept men’s accomplishments as proof of their abilities.174

Rooted in: Attribution bias

You realize that a colleague who is a man only mentors other men.

Why it matters

Mentorship can be critical to success.195 We all benefit when a colleague shows us the ropes or sponsors us for new opportunities—particularly when that colleague is more senior.196 If your coworker only mentors men, the women he works with are missing out on his advice and, potentially, on opportunities to advance. He is also missing out on their best thinking.

What to do

Talk to your colleague. Explain why mentoring is so valuable and share your observation that he only mentors men. Recommend he mentor at least one woman, and offer to help him identify a few promising candidates. If he confides he’s uncomfortable being alone with women, point out that there are plenty of public places to meet—and remind him that mentorship really matters.

Why it happens

We’re often drawn to people from similar backgrounds. The problem is that this can disadvantage people who aren’t like us—and this is especially true when we’re in positions of power.197 Additionally, some men are anxious about mentoring women for fear of seeming inappropriate. Almost half of men in management are uncomfortable participating in a common work activity with a woman, such as mentoring or working alone together.198

Rooted in: Affinity bias

A colleague advocates for a man with strong potential over a woman with proven experience.

Why it matters

When a more experienced candidate is passed up in favor of someone with less experience, your company can miss out on valuable wisdom, talent, and skill. And in this case, the woman loses out on an opportunity that she’s well suited for.

What to do

Point out how experienced the woman is for the role and note the value of proven experience over potential. You might also take a moment to explain WHY IT HAPPENS and WHY IT MATTERS.

Longer term, it’s worth recommending that everyone on your team aligns ahead of time on clear, objective criteria for open roles, then uses them to evaluate all job candidates. This minimizes bias by making sure that every candidate is held to the same standard.127

Why it happens

Research shows that people often hire or promote men based on their potential, but for women, potential isn’t enough. Women are often held to a higher standard and need to show more evidence of their competence to get hired or promoted.128

Rooted in: Performance bias

Your company announces its latest round of promotions. Nearly everyone moving up is a man.

Why it matters

This imbalance may signal bias in how your company evaluates employees for promotion—which means women may be missing out on valuable career opportunities and your company may be failing to get the strongest candidates into leadership positions. This is a widespread problem in corporate America: on average, women are promoted at lower rates than men, while Black women and Latinas are promoted at even lower rates than women overall.136

What to do

If you’re involved with reviews, seize the opportunity to make the process more fair. Suggest that your company set detailed review criteria up front and then stick to them.137 Consider using a rating scale (say, from 1 to 5) and ask reviewers to provide specific examples of what the employee did to earn each score.138 You can also suggest that your company set diversity targets for promotions, then track outcomes and monitor progress, which can also help move the numbers.139 If you’re not part of reviews, you can still make these suggestions to your manager.

Why it happens

Multiple forms of bias may contribute to a workplace in which fewer women are promoted. People tend to see women as less talented and competent than men, even when they’re equally capable.140 Because of this, women are less likely to get credit for successes and more likely to be blamed for failures.141

Rooted in: Performance bias, Attribution bias

You’re in a conversation with coworkers and someone without children asks a woman with children, “How do you manage work and raising your kids? You must be overwhelmed.”

Why it matters

This question reinforces an often unconscious belief that dedicated mothers can’t also be dedicated employees.281 It also assumes that the woman is overwhelmed, which can feel like a judgment on her ability to handle her workload and may lead to her getting passed over for opportunities. If this happens a lot, it can make women feel unsupported as working parents, which can make them more likely to leave the company.282

LeanIn.Org thanks Paradigm for their valuable contribution to this card

What to do

There are a few ways you can respond, based on what feels right. You can point out that feeling overwhelmed is something everyone experiences from time to time, whether or not they have kids. You can make the point that it’s not just working moms who have a lot to manage: “I imagine all working parents feel overwhelmed sometimes.” And if your colleague doesn’t seem overwhelmed to you at all, you can say that too.

Why it happens

Many people fall into the trap of believing that women can’t be fully committed to both work and family. That can fuel skepticism about women’s abilities. Fathers are often exempt from these assumptions.283

Rooted in: Maternal bias

A meeting is starting soon and you notice that it’s mostly men seated front and center and women seated to the side.

Why it matters

If women are sidelined in meetings, it’s less likely that they’ll speak up, which means the group won’t benefit from everyone’s best thinking. Plus, it’s not beneficial to sit in the low-status seats in the room—and women have to fight for status as it is.159

What to do

If there are empty chairs at the table, urge women sitting to the side to fill them. If there’s no room, acknowledge the problem—for example, ask if anyone else sees that it’s mostly men at the table. If it happens often, consider saying to the person who runs the meeting, “I’ve noticed that it’s mostly men at the table and women on the sidelines. Maybe you can encourage a better mix.”

Why it happens

Women typically get less time to speak in meetings. They’re more likely than men to be spoken over and interrupted.160 As a result of signals like these, women sometimes feel less valued, so they sit off to the side.

Rooted in: Performance bias

When discussing a potential promotion for a woman who uses a wheelchair, someone says, “I’m not sure she can handle a more senior role,” without offering further explanation.

Why it matters

The comment is vague and lacks evidence, which means it’s more likely to be rooted in bias. If it sways the team, it could mean this woman misses out on a promotion she is well qualified for. That hurts everyone, since teams with more diversity—including employees with disabilities—tend to be more innovative and productive.204

What to do

Ask the person to explain what they mean: “What parts of her qualifications don’t meet the criteria?”205 Basing evaluations on concrete criteria instead of gut feelings is fairer and can reduce the effects of bias. If you believe she merits a promotion, advocate for her. To help avoid bias in the future, you can talk to HR about using a set of clear and consistent criteria for promotions.206 You can also ask if your company has targets to recruit and promote more employees with disabilities.207

Why it happens

Research shows that people with disabilities face especially strong negative biases.208 In particular, women with disabilities are often incorrectly perceived as less competent than their coworkers, and their contributions may be valued less.209 They also get less support from managers than almost any other group of employees.210 This means they often face an uphill battle to advancement.

After an interview, a colleague says they didn’t like how a woman candidate bragged about her strengths and accomplishments.

Why it matters

In general, candidates who are well liked are more likely to be hired—so when women are seen as less likeable, they’re often less likely to get the job.251 And companies that fail to hire talented women miss out on their contributions and leadership.

What to do

Ask your colleague to explore their thinking: “That’s interesting. Do you think you’d have that reaction if a man did the same thing?” You can also reframe what happened: “I noticed that too, but I don’t see it as bragging. I just thought she was talking confidently about her talents.” It’s also worth pointing out that a job interview is exactly the place to talk about your strengths.

Why it happens

We expect men to assert themselves and promote their own accomplishments. But we often have a negative reaction when women do the same thing.252 This puts women candidates in a difficult spot. If they tout their achievements, it can hurt their chances of being hired. If they don’t, their achievements might be overlooked.

Rooted in: Likeability bias

A colleague mentions her wife during lunch with coworkers. The group conversation, which had been flowing nicely, abruptly goes silent.

Why it matters

Situations like this happen often to lesbian women, and they can create a barrier to connecting with coworkers.354 Regardless of intent, these silences signal discomfort with the fact that she’s married to a woman. Such moments can feel awkward and lonely, and if repeated could make your colleague feel unwelcome at work.

What to do

The most important thing to do is revive the conversation and signal support. Express genuine interest in your colleague and her family. Ask her what her wife does for work, whether they have kids, how they met, what they like to do on weekends … whatever you would ask a woman colleague married to a man.

Why it happens

There are several reasons why coworkers might fall silent at the news that a colleague is gay. Maybe they disapprove of marriage between two women. Or maybe their silence isn’t ill intentioned. They may have been surprised or hesitated because they want to show support but worry about saying the wrong thing.

You notice that your colleague, who is a woman, gets spoken over and interrupted more often than others during virtual team meetings.

Why it matters

It’s undermining to be repeatedly interrupted. It means that the team loses out on the woman’s ideas and insights. Plus, in a virtual context, meetings can carry more weight than they otherwise might. Without informal interactions in the office, virtual meetings become the central avenue for information sharing, brainstorming, and reputation building.

What to do

In the moment, you can use the chat feature to write something like, “Can we circle back to [Name]?” In the long run, encourage norms that promote equal participation, like everyone using the chat feature when they want to chime in. If you’re brainstorming, have people take turns and mute everyone except the speaker,387 or use a virtual brainstorming tool. You can also use breakout rooms to create smaller groups: one study found that women get similar amounts of airtime as men in groups of six or fewer, but less than men when in groups of seven or more.388

Why it happens

In general, women are interrupted far more often than men. Researchers believe that this happens just as often in virtual settings, if not more.389 This may be rooted in a common form of bias: people often value women’s contributions less highly than men’s.390

Rooted in: Performance bias

You offer the rising star on your team a stretch assignment, and she says she doesn’t feel qualified to take it on.

Why it matters

When women turn down opportunities they’re qualified for because of self-doubt, they miss out—and your company isn’t able to fully leverage their talents.

LeanIn.Org thanks Paradigm for their valuable contribution to this card

What to do

Let her know that you believe in her. Remind her she is being offered the opportunity because of her strong performance, not as a favor. You can also reassure her that how she’s feeling is perfectly understandable: “It’s normal for anyone to be nervous about taking on a bigger role. And women get sent signals that they’re not good enough. It’s hard not to internalize them.”

Why it happens

Women can be prone to more self-doubt than men, and it’s not because they’re missing a special confidence gene.170 Because we tend to underestimate women’s performance, women often need to work harder to prove they’re capable. And they are more likely to be passed over for promotions and stretch assignments. This bias is so pervasive that women often underestimate their own performance and are more likely than men to attribute their failures to lack of ability.171

Rooted in: Performance bias

A manager describes a woman who reports to her as “overly ambitious” when she asks for a promotion.

Why it matters

When a woman is criticized for competing for a promotion, it can have a negative impact on her and on the company as a whole. She may miss out on the chance to grow at work. Other women may hear the message that they shouldn’t ask for promotions. And the company may miss an opportunity to advance a talented team member and make her feel valued.

LeanIn.Org thanks Paradigm for their valuable contribution to this card

What to do

Prompt your colleague to explain her thinking. For example, you can say, “Generally, I think we like ambition as a company. Why does it bother you in this case?” You can also suggest that there may be a double standard at work by saying something like, “How do you feel when a man on your team asks for a promotion?” And if you think that women at your workplace are often criticized when they seek promotions, this would be a good opportunity to say so.

Why it happens

Because of stereotypical expectations that women should be selfless and giving, they can face criticism when they appear to be “out for themselves”—for example, when they compete for a bigger job.72 By contrast, we expect men to be driven and ambitious, and we tend to think well of them when they show those qualities.73

Rooted in: Likeability bias